Do dating teens think about marriage - join

Dating attitudes and expectations among young Chinese adults: an examination of gender differences

The Journal of Chinese Sociologyvolume 3, Article number: 12 (2016) Cite this article

65k Accesses

12 Citations

106 Altmetric

Metrics details

Abstract

While researchers have long examined the dating and mate selection patterns among young adults, the vast majority have utilized Western samples. In order to further our understanding of the changing nature of dating behaviors and attitudes, this study examines a sample of young Chinese adults and focuses upon the gender differences therein. Using a foundation of social exchange theory, the analyses illustrate the differences between the dating attitudes and expectations of Chinese women and men. Per traditional expectations, both sexes place a low priority on sexual behaviors, yet more progressive attitudes and behaviors are also evident. Women, in particular, appear to be more focused on pragmatic qualities in prospective partners. The influence of individualist values and the changing cultural norms pertaining to dating and familial roles are discussed.

Dating and romantic relationships are a normal, yet essential, part of life during the adolescent and early adult years. Beyond the basic desires which most individuals experience during this time, researchers have noted the relative significance of dating, not only for individuals but also for societies. The initiation and maintenance of intimate, romantic relationships have been linked with improved physical and emotional well-being, stronger perceptions of community attachment, and better developmental outcomes for the individuals (e.g., Amato 2010; Braithwaite et al. 2010; Proulx et al. 2007). During adolescence and the early adult years, dating enhances identity formation for individuals and provides socialization experiences which are necessary to forming and maintaining intimate and interpersonal relationships in life (Chen et al. 2009). Although researchers have directed their efforts toward a better understanding of the dynamics of dating and partner selection, focusing upon the influence of such elements as the family environment (e.g., parental divorce, parental marital quality, parent-child relationships), peer relationships, and community factors (Bryant and Conger 2002; Cui and Fincham 2010; Yoshida and Busby 2012), the majority of studies focusing upon dating and romantic relationships have utilized samples of Western youth.

In China, marriage and family life continues to be a central element within Chinese culture, with adolescents and young adults typically assuming that they will eventually find a partner. What is lacking, however, is a broader understanding of how contemporary Chinese youth view dating and intimate relationships. Researchers have noted this shortcoming and have called for greater empirical examination of partner selection in contemporary urban China (Xu et al. 2000) and particularly the attitudinal and expectational dimensions of dating (Hu and Scott 2016) and how these might vary by gender (Shek 2006). The present study will seek to address these calls for empirical study by using a sample of Chinese college students to examine the nature of attitudes and expectations concerning dating among young adults in contemporary China. The analyses which follow will attempt to more accurately discern the nature of such attitudes and expectations, as well as differences which may exist between females and males.

Dating and relationships

From a generational perspective, dating and romantic relationships in China are regarded differently, as adolescents and young adults may have more progressive beliefs, as compared to their parents. Researchers have noted that Chinese parents tend to oppose adolescent dating (Chen et al. 2009), perhaps due to their more traditional perspectives. While there is no clear definition of what is an appropriate age for individuals to begin dating, those who begin dating at early ages will typically have to cope with the opposition of parents (Wu 1996). Nonetheless, there is widespread acceptance that dating is becoming increasingly popular among Chinese youth (Tang and Zuo 2000).

Among Chinese college students, in particular, dating has quickly elevated in popularity (Yang 2011). Even the behaviors within dating appear to be rapidly changing over time. Behaviors such as holding hands and kissing in public, which may been somewhat taboo only a few decades ago, in China, are now becoming increasingly commonplace (Xia and Zhou 2003; Yang 2011). For such populations, who are often away from the eyes of their parents, college life may present opportunities for not only dating but also sexual activity (Xia and Zhou 2003). Lei (2005) reports that over one third of college students in China had become sexually active while enrolled in school. While dating and sexual activity among Chinese college students have been previously noted by researchers (e.g., Xu 1994), comparatively less is known about the attitudes and expectations of youth concerning these behaviors. In regard to premarital sex, for example, some studies have reported that 86 % of respondents approve of it (see Tang and Zuo 2000), while other studies have noted that vast majority of men want their brides to be virgins at the time of marriage (Ji 1990).

Seemingly, contemporary Chinese college students may be adopting a perspective of dating and intimate relationships which focuses less on paths toward marriage and more on immediate pleasure and gratification (Yang 2011). Much of this may also related to institutional changes, as the interpersonal relationships of students have been somewhat suppressed by colleges and universities (Aresu 2009). Universities commonly attempt to discourage sexual activity among students through educational programs and policies (Aresu 2009). Nonetheless, a comparison of college students in 2001 and 2006 revealed that self-reported premarital sexual intercourse rates went from 16.9 to 32 %, respectively (Pan 2007). Not surprisingly, Chinese parents tend to strongly discourage their daughters and sons from becoming sexual active, and many are opposed to their children being involved in dating relationships, at all (Stevenson and Zusho 2002).

The social and cultural context of dating

Aspects of dating, such as appropriate behaviors within dating and the appropriate age at which to begin dating, are greatly influenced by the larger social context in which they occur (Chen et al. 2009). Similarly, researchers have noted that attitudes and expectations concerning dating and intimate relationships are also affected by the larger cultural context (Hynie et al. 2006; Sprecher et al. 1994; Yan 2003). But China’s cultural context goes back several thousands of years. It has a written language that has been in use for the longest continuous period of time in the world, and it has the oldest written history (Han 2008). Thus, in order to best understand and appreciate the social dynamics occurring in present day China, one should first examine some of the important long-standing traditions connected to its culture.

The traditional expectations concerning dating and marriage have a long history within Chinese culture and are based heavily upon ancestor worship and Confucian ideology. From this perspective, filial piety and the continuation of family lineage are of tremendous importance (Han 2008). Hence, marriage (as the end goal of intimate relationships) is absolutely necessary and particularly so for males (Liu et al. 2014). One of the enduring cultural traits is “xiao,” which, in the most basic sense, refers to filial piety. The Chinese character for “xiao” can visually be interpreted as a child with an old man on his back (Han 2008). The long-standing expectation of “xiao” is that children devote their lives, without question, to their parents and families. This involves, especially for sons, the care for parents in their elderly years (see Ho 1996). Understandably, this places great pressure upon unmarried sons to negotiate with his parents over the identification and selection of a suitable wife, who, in turn, will also provide assistance to his aging parents. For sons, in particular, “xiao” makes finding a spouse a priority and consequently makes dating take on a different quality.

China is typically regarded as a collectivistic culture, in which obligations to the greater society and social institutions (e.g., the family) are considered more important than individual traits and needs (Kwang 2001; Ting-Toomey et al. 1991). Within individualistic cultures, romantic love is regarded as essential to marital satisfaction and well-being (Dion and Dion 1988). Hence, individual choice within dating relationships and mate selection processes is more likely to occur within individualistic cultures. Collectivistic cultures prompt young adults to regard love and romantic relationships within the larger context of their familial and societal obligations (Yang 1968). This, then, may lead young adults within collectivistic cultures to emphasize the pragmatic functions of dating and eventual marriage, while having less concern with notions of “love” and “romance” (Hsu 1981).

Following the end of the reign of Mao Tse-tung, along with the collapse of the former USSR, a fairly rapid pace of social, political, and economic changes occurred in China (e.g., Croll 2006; Tang and Parish 2000; Wang 2004). The post-Mao Chinese government has steadily encouraged economic modernization and the development of economic practices based upon free market principles similar to those found in Westernized countries. Social policies, such as the notable “One-Child Policy,” have been relaxed over recent years (Denyer 2015), allowing for individuals to better seek mates who are compatible in terms of number of children they desire to procreate. Whereas Chinese culture once emphasized the role of family in the selection of partners, with a strong tendency toward arranged marriages (Yang 1968), young Chinese adults now have greater choice in such decisions (Xu 1994). When combined with other changes, such as higher rates of educational attainment for women (Li 1994; Wu and Zhang 2010) and increased sexual activity among young adults (Feng and Quanhe 1996), it is likely that both culture preferences and actual behaviors concerning dating and mate selection may be undergoing substantial changes in China, as well.

The economic changes have had a considerable effect upon traditional family structures and behaviors. The collectivist nature of Chinese culture has been altered by economic factors in several substantial ways (see Yang 2011). First, there has been a steady shift away from collectivism toward individualism, causing people to give priorities to their own needs, rather than those of their family or larger society. Second, traditional marital relationships, often formed as a matter of practicality, have diminished and been replaced by a preference for relationships based on romance and Western notions of love. Finally, Chinese women, by virtue of their increasing educational and occupational attainment, now have greater economic independence, thus lowering their need to secure a spouse as a way of ensuring financial security. Hence, the traditional combination of marriage, sex, and family, as upheld by long-standing Chinese cultural expectations, has become less influential, particularly in regard to serving as a foundation of dating and partner selection.

Younger cohorts, who have had greater exposure to increasing individualism and Western culture, may approach dating and mate selection in a different manner from the previous generation. However, these younger cohorts must also recognize the existence of long-standing norms, as filial obligation remains a very tangible value in Chinese culture (Chui and Hong 2006), and continues to bind children to their parents. Indeed, recent studies have suggested that dating (Kim 2005) and decisions within marriage, itself, are still strongly affected by Chinese parents (Pimentel 2000). Given the relative paucity of research on dating and intimate relationships within China, it is difficult to accurately discern how these changes may be affecting young adults’ dating behaviors. When combined with other changes, such as migration, urbanization, income growth, increased social inequality, consumer culture, mass media, the Internet, and personal communication devices, some qualitative research suggest that both attitudes and actual behaviors concerning dating and mate selection are undergoing change in at least one of China’s largest cities. Research in Taiwan suggests that young adults are shifting their perspectives on dating and romance, away from traditional expectations (see Chang and Chan 2007). Zhang and Kline (2009), using a sample from mainland China, found that many young adults found their partner on their own accord but still maintained a desire to satisfy their parents’ wishes. In contemporary China, it is quite likely that both traditional expectations and newer, more modern attitudes concerning dating and partner selection are present. Whether one set of expectations is more influential, or if there is a merger or evolution of new attitudes concerning dating and partner selection, remains to be seen.

Gender and dating

Among Chinese youth, attitudes and expectations concerning dating and intimate relationships will also likely vary between females and males. In terms of dating and partner preferences, researchers have noted a considerable difference between the sexes, with a substantial double standard still prevailing (Piotrowski et al. 2016). For men, the ideal quality in a woman is beauty, while for women, the ideal quality in a man is intelligence (Xia and Zhou 2003). Generally, Chinese women are expected to marry at an earlier age, while they are still at the peak of their physical appearance and capacity to bear children, whereas men are expected to marry at a later age, after they have achieved financial success (Piotrowski et al. 2016). Recent studies suggest that stereotyped perceptions of young men and women exist (Jankowiak and Li 2014). Men are more often regarded as serious, ambitious, stubborn, deceitful, independent, and powerful, while women are viewed as quiet, anxious, excitable, gentle, depressed, shy, and jealous (Jankowiak and Li 2014).

In order to more fully comprehend these gender differences within Chinese culture, a much longer historical context must be considered. Gender ideologies in China have long been founded upon the general belief that women are supposed to be submissive and secondary to men (Bloodworth 1973). With Confucian philosophy, women are expected to maintain the three rules of obedience: (1) obeying their fathers and brothers prior to marriage, (2) obeying their husbands within marriage, and (3) as a widow, obeying their adult sons (Chia et al. 1997; Yang 1968). This set of beliefs, while seemingly outdated in contemporary society, is nonetheless one which has a very long existence within the Chinese culture. Indeed, several studies have suggested that even in the face of modernization and the influence of Western culture, traditional gender attitudes may persist. Researchers have found that many Chinese adults maintain traditional beliefs concerning the division of household labor (Cook and Dong 2011) and the responsibilities of child care (Rosen 1992). Males are still generally assumed to occupy the provider role within the family (Chia et al. 1997).

The relative roles and status of Chinese females and males have been patriarchal in nature for many centuries, yet these long-standing differences may be changing. In terms of educational attainment, for example, women’s educational attainment rates, which had previously lagged far behind those of men, are now rising. Indeed, both in terms of enrollment and completion rates, women now exceed men in Chinese colleges and universities (Wu and Zhang 2010). Women’s employment, which has always been guaranteed within China, is on par with that of men. Higher levels of educational attainment, coupled with comparable employment and earnings levels, may lead Chinese women to maintain more egalitarian attitudes concerning gender and gender roles. How these gendered expectations affect contemporary dating attitudes and behaviors, though, is yet unknown.

While addressing gender-related issues which may affect the dating and mate selection patterns of young Chinese adults, it is equally necessary to address the sex ratio of the population, itself. One lasting effect of the one-child policy, when combined with the traditional preference for sons, is that the current adult population contains more males than females. Currently (based on 2010 census data), the sex ratio for the population of never-married individuals, 15 years of age and above, is 134.5 (Liu et al. 2014). Despite the recent changes to the one-child policy, the skewed sex ratio is expected to create a male marriage “squeeze” for at least a few more decades, thus making it difficult for the current adult male population to find a wife (Guilmoto 2012). It is quite likely that the sex ratio will have an impact, not only upon mate selection but also the preceding dating behaviors. South and Trent (2010) have noted that the sex ratio imbalance is associated with higher levels of premarital sex among Chinese women but is associated with lower levels of premarital sex among men.

Understanding gender differences in dating

Numerous perspectives have been offered as attempts to explain gender differences which have been identified within dating and intimate relationships. Buss and his colleagues (Buss et al. 1990; Buss 2003) have suggested that there is an evolutionary basis for such differences. Males, in this perspective, will seek females with greater physical attractiveness, youth, and chastity, while females will seek out males with greater resources (i.e., financial), intelligence, and ambition. Male preferences will be based upon their desire to obtain a suitable mating partner, for the purpose of bearing offspring, while female preferences will be based upon their desire for a provider/protector. Although this perspective has generated considerable debate, it does not readily address differences which may results from a specific cultural context.

Exchange theory may provide a foundation for better understanding the nature of dating and partner selection in China. Parrish and Farrer (2000) posit that gender roles within China have undergone considerable change, due to both micro-level mechanisms of bargaining (e.g., within couple’s relationships) and macro-level shifts in existing social institutions (e.g., educational and occupational institutions). Given the dramatic increases in both Chinese women’s educational attainment and greater occupational attainment, they now have greater status in many situations, specifically in regard to bargaining and decision-making within personal relationships (Gittings 2006; Guthrie 2008). From a historical perspective, the New Marriage Law of 1950 helped to set into motion a shift toward improved statuses for women, by legalizing gender equality and freedom of choice in both marriage and divorce. These improvements have, in turn, set the stage for a considerable shift away from more traditional forms of dating and mate selection and have also made the potential “Westernization” of ideologies surrounding romance and dating relationships even more likely (Hatfield and Rapson 2005).

The imbalanced sex ratio may also create an environment in which women have even greater influence, particularly in regard to dating and mate selection. Assuming a strong preference for marriage, exchange theory would again support the notion that women, as the smaller population, would have a decisive advantage. The dyadic power thesis (see Sprecher 1988) posits that, in this instance, the relative scarcity of women increases their dyadic power within relationships (see also Ellingson et al. 2004). Hence, women would not only have greater control over the selection of a partner but also wield greater decision-making power within the relationship. This perspective is supported by recent studies which show that Chinese women have become increasingly selective in the marriage market, preferring men with higher salaries, more prestigious occupations, and better living quarters (Liu 2005). Within the context of dating and intimate relationships, men with less social capital (e.g., educational attainment, income, desirable housing) may find it increasingly challenging to find a date, much less a spouse (see Peng 2004). Understandably, the cultural expectation held by Chinese men that women should be docile and tender may greatly complicate men’s search for a partner, as Chinese women’s greater selection power, coupled with changes in the broader culture of dating, may directly counter long-standing gendered expectations (see Parrish and Farrer 2000).

Research questions and hypotheses

Given China’s record setting leap into becoming a industrialized country in just a matter of decades on top of having a very ancient cultural history which serves as a source of pride, one would half expect China’s traditional culture to “stand strong like bamboo” or, at worse, perhaps bend a bit. On the other hand, one would expect something to give under such complete and rapid societal change. Young Chinese students should be the members of society who would be most willing to abandon traditional Chinese values and the associated behavioral processes which control dating (and marriage) and move toward adopting Western style patterns where familial relationships are forged out of affective individualism. Under this approach, marriages are based largely on love type feelings and the decision about whom to marry resides mostly with the individual. In an increasingly stratified society, the actors might feel most comfortable seeking out life partners who occupy similar positions within the social structure (i.e., education level, social class, occupational prestige, ethnicity). This process is called homogamy.

Hypothesis 1

The dating behavior of students should not be strongly influenced by parents who continue to hold a traditional perspective. In other words, elements of affective individualism should manifest themselves.

An adolescent youth subculture is on the rise in China, and hence, the influence of peers on the dating and courtship behaviors of individuals will increase and eventually become stronger than that of the family. In the power vacuum caused by the decline of parental influence, young people will most likely fill the void as the culture becomes less backward looking and more forward looking.

Hypothesis 2

Peers and the adolescent subculture, as opposed to parents, should exert a significant influence on the dating behavior of Chinese youth.

Chinese culture is thousands of years old. Thus, one should not expect the traditional, conservative, patriarchal Chinese values will completely disappear among present day Chinese youth and hence have no impact on dating relationships. Cultural rebels—male and female—will be present, exploring the uncharted cultural waters. However, cultural conformists who are reluctant to abandon family and tradition will maintain some degree of cultural continuity across time and generations.

Hypothesis 3

Since culture and gender relations are generally resistant to rapid change in society, centuries old traditional gender role attitudes should be found to continue to persist among significant numbers of Chinese youth.

To the extent that traditional values about dating and relationships impact the decision-making process, they may also be imbedded in the types of personal qualities that singles are looking for in their potential mates. If traditional values continue to exert an influence on thinking and behavior despite changes in the social context, then males and females will gravitate toward different criteria. Also, comparative research on partner preferences finds that preferences fall into three broad or seemingly universal categories: physical, practical, and personal. The extent to which these three categories are gendered is not addressed in the literature. However, we expect to find them operating in our study population and to be gendered.

Hypothesis 4

Patterns in partner preferences which have been found across societies should be present among Chinese youth, namely, concern about physical appearance, economic prospects, and kind or compassionate personality of future potential spouses.

In addition to the above broad hypotheses, we also expect older students and those who are religious to be slightly more conservative. Students who perform well academically might use that strength as a bargaining chip. Men could use it as an asset to be sold on the dating and marriage market while women could use it as a signifier of them possessing egalitarian values and seeking like-minded mates. It should be noted that in the USA, students who exhibit high levels of dating behavior in high school are less likely to be academic high achievers.

Data and methods

Data for this study were collected during the summer of 2015 at a large public university in Shanghai, China. A random sample of students were approached and asked to participate in a survey concerning dating and romantic relationships. Of those approached, 87 % agreed to participate and completed the survey. After tabulation of the responses, 17 cases were eliminated due to incomplete responses, resulting in a sample of 341 students (191 females and 150 males). The students ranged in age from 18 to 22 and were all currently enrolled at the university. All of the students in the sample were single and never married. Among females, 44.5 % described themselves as “currently dating someone,” while 54.0 % of males described themselves as likewise.

A variety of questions were used to assess respondents’ attitudes, preferences, and aspirations concerning dating and intimate relationships. In regard to dating, respondents were asked to respond to the statement, “I would like to date more frequently than I do now.” Responses ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Participants were also queried concerning their willingness to either kiss or have sex on a first date. Respondents were offered the statements: (1) “I would be willing to kiss on a first date” and (2) I would be willing to have sex on a first date.” Responses again ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Together, these items provide a broad range of assessment concerning dating and intimate relationships.

Respondents were also asked about a variety of family and individual characteristics. In terms of their parents, participants were asked about the educational attainment of their mothers and fathers. The higher of the two (when two parents were present) was then included as a measure of the highest parental education, with responses including “eighth grade or less” (1), “beyond the eighth grade but did not complete high school” (2), “high school degree” (3), “attended college but did not finish degree” (4), “four-year college degree” (5), and “graduate or professional degree” (6). Maternal employment was also assessed, with respondents being queried about whether their mother was employed for pay outside the home (yes = 1, no = 0). Since the familial context is likely to influence both dating and marriage patterns among young adults, participants were asked: “For most of the time when you were growing up, did you think your parents’ marriage was not too happy (1), just about average (2), happier than average (3), or very happy (4).” Since western culture could potentially affect dating and marriage patterns among Chinese young adults, the respondents were also queried as to whether English was spoken in their homes (1 = yes, 0 = no). In regard to parental influence, participants were offered the following statement: “I would be willing to date someone of whom my parents/family did not approve.” Responses ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

Individual characteristics were also examined within the survey. Respondents were asked to provide their age and sex but were also asked a variety of other questions related to their own traits. Respondents were asked how often they attended religious services, with responses ranging from “do not attend” (1) to “once or more per week” (6). A basic measure of self-esteem was included, using responses to the statement: “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.” Responses ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). In regard to attitudes, respondents were asked about their beliefs concerning gender roles within the family context. The statements used in creating an index of gender attitudes included the following: (1) it is much better for everyone if the man earns the main living and the woman takes care of the home and family, 2) both husbands and wives should contribute to family income, 3) a husband should spend just as many hours doing housework as his wife, and 4) the spouse who earns the most money should have the most say in family decisions. Responses to each of these statements ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” After inverting the coding schemes, the resultant combined measure of gender attitudes ranged across a five-point scale, with a higher score indicating more conservative/traditional gender role attitudes (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89). Respondents were similarly asked about their pro-natalist attitudes by being asked to respond to the statement: “a person can have a fully satisfying life without having children.” Responses ranged from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (5). A measure of school performance was also included, with respondents describing their overall grade performance. Responses ranged from “less than D’s” (1) to “mostly A’s” (8).

Given the complex nature of dating and dating relationships, multiple measures were utilized in these analyses. In regard to dating experiences, respondents were asked “thinking back about all of the dating experiences you’ve had, how long was the longest romantic relationship you have had?” Responses to this item ranged from “less than a week” (1) to “more than a year” (9). A measure of respondents’ willingness to date outside of their own social groups was included through the combination of responses to three different questions. Respondents were asked if, in terms of dating partners, they would be willing to date someone from (1) a different religion, (2) a different race or ethnicity, and (3) a different country. The responses to each item ranged from “yes,” “no,” and “maybe.” Affirmative responses (“yes”) to each were then combined to create a measure of desired heterogamy (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87), with a range of 0 to 3. Participants were asked how many of their close friends were currently dating or in a romantic relationship. Responses to this question ranged from “only a few or none of them” (1) to “all or almost all of them” (5). Participants were subsequently asked about the specific characteristics which they are looking for in a partner. Respondents were asked to indicate their preference for particular traits by stating whether each quality was “not at all important” (1) to “extremely important” (7). Of the particular traits which were queried, some were used to create indexed measures of a broader set of characteristics. The first of these, pragmatic, is created through the combination of four traits: well educated, wealthy, successful, and ambitious (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). The second, caring, is created through the combination of the following four traits: affectionate, loving, considerate, and kind (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86). The third, appearance, is created from the combination of four traits: sexy, neat, attractive, and well dressed (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87). Together, these three measures provide a broader assessment of qualities which the respondents might desire in a potential partner.

Results

Table 1 presents the mean levels of dating and marriage characteristics among young Chinese adults, by sex. As shown, an overwhelming majority of both young women and men would prefer to date more frequently. Approximately 66 % of women and 71 % of men expressed the desire to date more often. Given the age of participants in the sample, this is to be expected. In terms of dating behaviors, however, significant differences are shown between the two sexes. Respondents were queried about their willingness to kiss on a first date. Here, significantly more men, as compared to women, stated that they would be willing to kiss on a first date. It should be noted, nonetheless, that approximately 39 % of Chinese women and 42 % of men did not express a willingness to kiss on a first date. This finding would appear to suggest the more traditional Chinese cultural expectations pertaining to dating are still influencing dating attitudes and behaviors among contemporary young adults. This possibility is further enforced by the responses shown in regard to participants’ willingness to have sex on a first date. Although young Chinese men are shown to be significantly more willing to have sex on a first date, as compared to young women, almost two thirds of the women and more than a third of the men stated that they would not do so. Hence, while young men may be significantly more likely to be willing to kiss and/or have sex on a first date, as compared to women, it would appear that many, if not most, young men still adhere to a more traditional or conservative approach to dating.

Full size table

Table 2 presents the mean levels of family and individual characteristics among young Chinese adults, by sex. As shown, the parents of both young women and men were reported to have a relatively high level of educational attainment, with the typical parent having at least some college. Among women, approximately 83 % reported that their mother was employed outside the home, while the corresponding employment rate among men’s mothers was 77 %. Both young women and men reported that their parents had relatively high marital quality. Assuming that these responses are reliable, it would suggest that most young Chinese adults have had positive role models concerning spousal roles and relationships. English was spoken only in a small percentage of homes (13 % of women’s families and 14 % of men’s). Familial influence appears to be slightly less influential among young men, as significantly more reported that they would be willing to date someone without their parents’ approval, as compared to women. This finding is somewhat intriguing, as given the patriarchal nature of Chinese culture, one might anticipate parents being more cautious and involved in the dating behaviors of their sons, as compared to daughters.

Full size table

Men in the sample were shown to be slightly older than the women (20.69 versus 20.31 years of age, respectively). In regard to religiosity, most respondents reported participating in religious activities only a few times each year. Self-esteem levels reported by the respondents were moderately high, with no significant differences shown between women and men. Neither sex appeared to be overly anxious to become parents, as their relative responses to the query concerning pro-natalist attitudes was somewhat low. This is not entirely unanticipated, as one would tend to believe that college students do not place parenthood high among their priorities at their age. It is worth noting that young men do espouse significantly more conservative attitudes concerning gender and gender roles within the family, in particular. Again, given the more patriarchal nature of Chinese culture, this is to be expected.

In terms of dating, young men reported having had longer relationships in the past, as compared to young women. In order to put this in context, however, it should be noted that the men’s longest relationships, on average, had lasted only a few months. Approximately half of the friends of both women and men were reported to be currently dating. Hence, there is a potential for considerable peer pressure, in regard to dating behaviors. In regard to potential dating partners, young Chinese women and men appear to be only marginally willing to consider partners from outside their own social groups (i.e., religion, race/ethnicity, and nationality). This may be a reflection of the lack of diversity within China and certainly as compared to countries with more diverse populations.

Table 3 presents the mean levels of desired partner characteristics, as presented for females and males. In terms of specific partner characteristics, young women expressed a significantly higher preference for pragmatic qualities, as compared to men (4.90 versus 4.33, respectively). Across all four of the components, females’ preferences in a male partner where significantly higher than those of their male counterparts. Females expressed a significantly higher preference for a male partner who is well educated, wealthy, successful, and ambitious. While not statistically significant, women also expressed a slightly higher preference for caring qualities. It is necessary to note, however, that females did express a significantly greater preference for a male partner who was kind, as compared to their male counterparts’ same preference in a female partner. In regard to appearance, while men expressed a slightly higher preference for appearance qualities, as compared to women, the difference was not significantly different, overall. Men did express a significantly higher preference for a female partner who is “sexy,” as compared to the preferences expressed by women for the same quality in a male partner. Overall, these desired characteristics seem to support previously noted gender stereotypes, with women expressing a stronger preference for more pragmatic qualities in a partner, while men, to a lesser extent, express a stronger preference for physical appearance. We will now examine how these various factors affect dating and intimate relationships characteristics.

Full size table

Table 4 presents the results of ordinary least squares regression models of dating characteristics among young Chinese adults. The models are presented separately for each sex, for each characteristic, so as to allow for a more direct comparison of the effects of familial and individual traits. Previous analyses (not shown) were performed to ascertain the need for separate models for each sex. In regard to wanting to date more frequently, females whose parents have a higher level of educational attainment are shown to have a lower desire to date (b = −.104). Given that Chinese culture places a premium upon educational attainment (Stevenson and Stigler 1992), this association may result from parents’ desire to see their children succeed (i.e., placing greater emphasis upon education, as opposed to intimate relationships). Females’ levels of self-esteem are positively associated with wanting to date more frequently (b = .143), suggesting that self-assurance and confidence may play a substantial role in the dating patterns of young Chinese women. In a similar manner, women’s pro-natalist attitudes are positively associated with wanting to date more frequently (b = .140). In regard to desired spousal qualities, a stronger desire for pragmatic qualities is significantly associated with wanting to date more often (b = .239). The strength of this association may imply that Chinese women not only desire more pragmatic qualities in a spouse but perhaps also view dating itself in more pragmatic manner. Caring qualities, such a loving and kind partner, also yield a significant association with women’s wanting to date more frequently (b = .155), but the association is relatively meager. Finally, women’s desire for appearance qualities is shown to be negatively associated with wanting to date more frequently. Hence, women who place a greater premium upon physical appearance may actually be less likely to want to date more often.

Full size table

In the comparable model of men’s wanting to date more often, pro-natalist attitudes yield a negative association (b = −.147), which is opposite to the same effect shown in the model for women. It is quite possible that men who espouse more pro-natalist attitudes (i.e., desire children) may be more selective in their dating behaviors, thereby reducing their desire to date many women. Young Chinese men who place more emphasis upon caring qualities in a spouse (b = .377), on the other hand, are shown to have a greater desire to date often. This difference between women’s preference for pragmatic qualities and men’s preference for caring qualities will be addressed more fully in the discussion section.

Among women, parental educational attainment is significantly associated with the willingness to kiss on a first date (b = .220). It is possible that higher parental educational attainment may also be linked with more progressive attitudes and expectations about dating, on the part of parents. Not surprisingly, women who state a willingness to date without parental approval are shown to be significantly more likely to kiss on a first date (b = .233). Within the context of Chinese culture, both of these are likely to be considered progressive and contrary to traditional standards of behavior for young women. Young women also appear to be readily affected by their friends, as the number of friends dating is positively associated (b = .190) with a willingness to kiss on a first date. However, self-esteem yields a negative association with women’s willingness to kiss on a first date (b = −.169), as does pro-natalist attitudes (b = −.147). Among young men, parental educational attainment reveals a negative association (b = −.156), which is directly contrary to the effect shown in the model for women. Clearly, the impact of parental characteristics varies, depending upon whether they involve sons or daughters. Older males are more likely to kiss on a first date (b = .127), as are those who attend religious services more frequently (b = .186). It is noteworthy that the desire for heterogamous relationships is positively associated with the willingness to kiss on a first date (b = .219) among men, yet the same positive association is also shown in regard to conservative gender attitudes (b = .381). This may possibly suggest that young men with a more traditional set of attitudes wish to have both ways—to date outside of their own social groups—yet maintain a more traditional (i.e., patriarchal) role within the relationship.

In regard to women’s willingness to have sex on a first date, the willingness to date without parental approval yields a positive association (b = .323), as does the number of friends who are dating (b = .203). Since having sex on a first date represents a more tangible breech of traditional standards, it is logical that women must also be willing to break away from parents’ expectations. Along the same vein, having friends who are also dating may provide the social support and reinforcement which make having sex on a first date seem more acceptable to young Chinese women. However, women’s self-esteem, along with their pro-natalist attitudes, yields negative associations with the willingness to have sex on a first date (b = −.195 and −.197, respectively). Having higher self-esteem, then, may provide women with the confidence or security to not have sex on a first date, whereas lower levels of self-esteem may bring about the opposite. The stronger desire to have children, likewise, may lead young women to be more selective in their dating behaviors or perhaps they may be more likely to associate sex with a more stable and lasting relationship (such as marriage). Among males, the overall robustness of the regression model is not as strong. However, conservative gender attitudes are shown to be positively associated with men’s willingness to have sex on a first date (b = .357). Again, this may be related to the patriarchal roles found within broader Chinese culture, such that young men with more traditional gender attitudes may believe that they should assume a stronger role in the decision-making behaviors involved in dating and dating relationships. The implications of these findings will now be addressed.

Discussion and conclusions

This study was initiated to provide an exploration of dating and mate selection traits among young adults in contemporary China. The sample used for these analyses is a relatively small and select one and does not necessarily provide for making broad generalizations to the larger population of young adults in China. However, the findings shown herein do offer fresh insight into both the nature of dating experiences and some of the pertinent gender differences which exist.

Overall, both young Chinese women and men expressed a desire to date more frequently, suggesting that the more progressive notions of love and romance may be taking hold within Chinese culture. With the increasing influence of individualism and consumerism, it is not entirely unexpected that Chinese youth should wish to emulate behaviors which they believe to be more “modern” or “western.” Despite their seeming eagerness to be more active in seeking dating partners, there also appears to be considerable adherence to more traditional culture expectations. Specifically, only the minority of both females and males expressed a willingness to have sex on a first date. This pattern is certainly more consistent with traditional expectations concerning what is appropriate behavior for young adults in intimate relationships. As expected, significantly more males than females expressed the willingness to have sex on a first date, yet even among males, more expressed opposition, rather than a willingness to do so. This would again seem to support the existence of long-standing expectations concerning dating. Unlike more westernized beliefs concerning dating, sex and sexual behavior still appear to be outwardly undesired by young Chinese adults of either sex. This conclusion is further supported by the unwillingness of both females and males to kiss on a first date. Once again, more males expressed a willingness to do so, yet substantially more males were clearly opposed to this. While these data are intended to provide an exploratory examination of dating attitudes and behaviors, these findings do suggest that both traditional and more progressive elements are concurrently present in the dating traits of contemporary Chinese young adults.

Gender differences were also noted in regard to the desired partner characteristics, as expressed by females and males. In keeping with long-standing gender stereotypes, females did express a greater preference for more pragmatic qualities in a male partner (i.e., well educated, wealthy, successful, and ambitious). This supports previous research which has noted such gender-based distinctions. Chinese men, on the hand, only partially conformed to the gender stereotypes for males. Although men did express a greater preference for a “sexy” female partner, no significant differences were shown for the other attributes related to appearance. Hence, while it would appear that a double standard does exist in regard to desired partner attributes, the more stereotyped expectations are found among women and less so among men.

The multivariate models yielded several rather intriguing findings. In particular, it was shown that Chinese women have a greater desire to date more frequently when they have more pragmatic desires in a prospective partner. Chinese men, on the other hand, have a greater desire to date more frequently when they desire a partner with more caring qualities. On the surface, these two patterns offer some substantiation of the traditional gender-typed beliefs that men are seeking love and romance from dating (and from eventual marriage), while women are perhaps regarding dating as a pathway to marriage and the subsequent security (e.g., financial) offered within. Obviously, additional study is necessary in order to more accurately discern and understand these patterns. These findings do lend support to exchange theory, as each sex does appear to be approaching dating and intimate relationships with somewhat different perceptions and goals.

The potential for more progressive (and westernized) traits can also be seen within the models concerning kissing and having sex on a first date. Among females, the regression models revealed that a willingness to date without parental approval (which would be directly counter to traditional cultural expectations) was shown to be associated with a greater willingness to both kiss and have sex on a first date. Essentially, breaking away from parental control is associated with greater sexual expression among young Chinese women. This would certainly be consistent with a tendency toward greater individualism, as suggested previously. In addition, women were shown to be more likely to kiss and/or have sex on a first date when they had more friends who were also dating. Once, again, this suggests a strong peer influence, perhaps part of a broader new youth subculture, which is generally considered to be antithetical to parental and familial influence. Finally, women with pro-natalist attitudes (i.e., seeking to have children, one day) were shown to be considerably less willing to kiss and/or have sex on a first date. If the maternal role can be considered to be a more traditional role for women, it would appear that young Chinese women are giving significant priority to the later role of motherhood, as opposed to indulging in more immediate sexual behaviors in the context of dating.

Overall, these findings suggest that contemporary Chinese youth are perhaps forging a path somewhere between the expectations of traditional Chinese culture and the more progressive expectations of an ever-changing modern society. Youth are often at the “cutting edge” of social change, and their attitudes and expectations are often portrayed as being directly contradictory to and even boldly challenging those of their parents. These results do not suggest that a polarized set of expectations are present; instead, it would appear that Chinese youth have found a balance between the two and appear to be content with the combination. As stated previously, while researchers have directed considerable efforts toward better understanding the nature and dynamics of dating and mate selection among young adults, most of these efforts have involved Western samples. Hence, much of the theory and conceptual knowledge may not necessarily apply to non-Western samples. In particular, the appropriateness of applying of such existing theories and concepts to Asian cultures has been called into question (Ho et al. 2012). The rapid economic and social change which is occurring in urban centers of China, such as Shanghai, will eventually be evident within the rest of the population, especially as the residential distribution shifts from a rural to an urban majority. Researchers should attempt to address how these ever-shifting social, economic, and political changes will affect not only the dating experiences among the young adult population but also familial structures and behaviors in the longer term.

References

Amato, P. 2010. Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family 72: 650–666.

Article Google Scholar

Aresu, A. 2009. Sexuality education in modern and contemporary China: Interrupted debates across the last century. International Journal of Educational Development 29: 532–541.

Article Google Scholar

Bloodworth, D. 1973. The Chinese looking glass. New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

Google Scholar

Braithwaite, S.R., R. Delevi, and F.D. Fincham. 2010. Romantic relationship and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships 17: 1–12.

Article Google Scholar

Bryant, C.M., and R.D. Conger. 2002. An intergenerational model of romantic relationship development. In Stability and change in relationships, ed. A.L. Vangelisti, H.T. Reis, and M.A. Fitzpatrick, 57–82. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Buss, D.M. 2003. The evolution of desire: Strategies of human mating. New York: Basic Books.

Google Scholar

Buss, D.M., M. Abbot, A. Angleitner, and A. Asherina. 1990. International preferences in selecting mates. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 21: 5–47.

Article Google Scholar

Chang, S., and C. Chan. 2007. Perceptions of commitment change during mate selection: The case of Taiwanese newlywed. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 24(1): 55–68.

Article Google Scholar

Chen, Z., F. Guo, X. Yang, X. Li, Q. Duan, J. Zhang, and X. Ge. 2009. Emotional and behavioral effects of romantic relationships in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 38: 1282–1293.

Article Google Scholar

Chia, R.C., L.J. Allred, and P.A. Jerzak. 1997. Attitudes toward women in Taiwan and China. Psychology of Women Quarterly 21: 137–150.

Article Google Scholar

Chui, C.Y., and Y.Y. Hong. 2006. Social psychology of culture. New York: Psychology Press.

Google Scholar

Cook, S., and X. Dong. 2011. Harsh choices: Chinese women’s paid work and upaid care responsibilities under economic reform. Development and Change 42: 947–965.

Article Google Scholar

Croll, E. 2006. China’s new consumers: Social development and domestic demand. London: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Cui, M., and F.D. Fincham. 2010. The differential effects of parental divorce and marital conflict on young adult romantic relationships. Personal Relationships 17: 331–343.

Article Google Scholar

Denyer, S. 2015. China lifts one-child policy amid worries over graying population. The Washington Post, October 29. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-lifts-one-child-policy-amid-worries-of-graying-population/2015/10/29/207fc0e6-7e2b-11e5-beba-927fd8634498_story.html.

Dion, K.L., and K.K. Dion. 1988. Romantic love: Individual and cultural perspectives. In The psychology of love, ed. R.J. Sternberg and M.L. Barnes, 264–289. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Google Scholar

Ellingson, S., E.O. Laumann, A. Paik, and J. Mahay. 2004. The theory of sex markets. In The sexual organization of the city, ed. E.O. Laumann, S. Ellingson, J. Mahay, A. Paik, and Y. Youm, 3–38. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Feng, W., and Y. Quanhe. 1996. Age at marriage and the first birth interval: The emerging change in sexual behavior among young couples in China. Population and Development Review 22(2): 299–320.

Article Google Scholar

Gittings, J. 2006. The changing face of China: From Mao to market. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Guilmoto, C.Z. 2012. Skewed sex ratios at birth and future marriage squeeze in China and India, 2005-2100. Demography 49(1): 77–100.

Article Google Scholar

Guthrie, D. 2008. China and globalization: The social, economic and political transformation of Chinese society. New York: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Han, J. 2008. Chinese characters. Beijing: China Intercontinental Press.

Google Scholar

Hatfield, E., and R.L. Rapson. 2005. Love and sex: Cross-cultural perspectives. New York: Allyn & Bacon.

Google Scholar

Ho, D.Y.F. 1996. Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In Chinese psychology, ed. M.H. Bond, 155–165. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Ho, M.Y., S.X. Chen, M.H. Bond, C.M. Hui, and M. Friendman. 2012. Linking adult attachment styles to relationship satisfaction in Hong Kong and the United States: The mediating role of personal and structural commitment. Journal of Happiness Studies 13: 565–578.

Article Google Scholar

Hsu, F.L. 1981. Americans and Chinese: Passage to difference. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii.

Google Scholar

Hu, Y., and J. Scott. 2016. Family and gender values in China: Generational, geographic, and gender differences. Journal of Family Issues 37(9): 1267–1293.

Article Google Scholar

Hynie, M., R.N. Lalonde, and N. Lee. 2006. Parent-child value transmission among Chinese immigrants to North America: The case of traditional mate preferences. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 12(2): 230–244.

Article Google Scholar

Jankowiak, W., and X. Li. 2014. The decline of the chauvinistic model of Chinese masculinity. Chinese Sociological Review 46(4): 3–18.

Article Google Scholar

Ji, Y. 1990. The revelation of life. Taiwan: Beiyue Wneyi Chubanshe.

Google Scholar

Kim, J.L. 2005. Sexual socialization among Asian Americans: A multi-method examination of cultural influences (Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, 2005).

Google Scholar

Kwang, N.A. 2001. Why Asians are less creative than westerners. New York: Prentice Hall.

Google Scholar

Lei, Y. 2005. Love and reason in the ivory tower: Report on investigating issues concerning dating and love among contemporary college students. Zhenzhou: Henan University Press.

Google Scholar

Li, E.B.C. 1994. Modernization: Its impact on families in China. In Marriage and the family in Chinese societies: Selected readings, ed. P.L. Lin, K. Mei, and H. Peng, 39–44. Indianapolis: University of Indianapolis Press.

Google Scholar

Liu, Z. 2005. The inspiration from a village. China’s National Conditions and Strength 11: 41–43.

Google Scholar

Liu, L., X. Jin, M.J. Brown, and M.W. Feldman. 2014. Involuntary bachelorhood in rural China: A social network perspective. Population 69(1): 103–126.

Article Google Scholar

Pan, S.M. 2007. The incidence of Chinese college students. Beijing: Chinese people’s sexual behavior and sexual relationship: Historical development 2000-2006. Retrieved from http:/blog.sin.com.cn/s/blog_4dd47e5a010009j2.html.

Google Scholar

Parrish, W.L., and J. Farrer. 2000. Gender and family. In Chinese urban life under reform: The changing social contract, ed. W. Tang and W.L. Parish, 232–270. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Peng, Y. 2004. An exploration into the phenomenon of involuntary bachelors in poverty-stricken area. Youth Studies 6: 18–20.

Google Scholar

Pimentel, E.E. 2000. Just how to I love thee? Marital relations in urban China. Journal of Marriage and Family 62: 32–47.

Article Google Scholar

Piotrowski, M., Y. Tong, Y. Zhang, and L. Chao. 2016. The transition to first marriage in China, 1966-2008: An examination of gender differences in education and Hukou status. European Journal of Population 32: 129–154.

Article Google Scholar

Proulx, C.M., H.M. Helms, and C. Buehler. 2007. Marital quality and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 576–593.

Article Google Scholar

Rosen, S. 1992. Women, education, and modernization. In Education and modernization: The Chinese experience, ed. R. Heyhoe, 255–284. Exeter: Pergamon.

Google Scholar

Shek, D.T.L. 2006. Chinese family research puzzles, progress, paradigms, and policy implications. Journal of Family Issues 27: 275–284.

Making Sense of Teen Dating Lingo

If you feel like you need a translator when you hear your teen talk about their dating relationships, you are not alone. The majority of parents struggle to make sense of the words teens use, like ghosting or cuffing, to describe what is happening in their world.

But if you want to provide insight and advice when they are talking to you, it is important that you have a good grasp of what it means if your teen says their significant other is "ghosting" them or has "left them on read."

Common Terms

No longer is it enough for parents to know just what sexting is. Now, you need to add in "benching," "53X," and so many more terms to your vocabulary.

The digital world has created an entirely new language of love that threatens to leave parents in the dark unless they essentially become bilingual. Here is a parent's guide to your teen's dating terminology.

Ghosting

Ghosting occurs when someone your teen is dating suddenly stops contacting them. It is usually the result of this other person being too afraid to tell your teen that they do not want to take things any further or that they want to end the relationship.

So, instead of communicating directly, they start behaving like a ghost. When this happens, your teen often checks their phone incessantly looking for a response back, a text, or some sign of life.

Zombieing

Zombieing occurs when the person who ghosted your teen suddenly makes an appearance in their life again. It is like they have come back from the dead.

In other words, the person will suddenly start liking or following your teen's social media, texting, or displaying some interest in your teen but not giving a full-on approach to rekindling the relationship.

Slow Fade

This approach is supposedly a kinder, gentler way to ghost someone by slowly fading from the picture. When a slow fade happens, your teen's love interest gradually fades away by making less and less effort to connect. The end result is longer and longer amounts of time between replies.

Cuffing

Cuffing most often occurs during the winter months when teens are looking to get in a committed relationship. The goal is to have a boyfriend or girlfriend over the holidays and on Valentine's Day.

Teens may use this term to describe a friend who is seeking out a significant other so they are not alone on romantic holidays.

Curving

When teens use the term curving, they are talking about rejecting someone's romantic interest in them. They could also use it to talk about how someone responded to them. The teen may answer messages inconsistently or take a suspiciously long time to reply, then provide mild excuses for their lack of response.

DTR

DTR stands for "define the relationship." When teens use this term, they want to have a conversation with their significant other about where the relationship is headed.

Are they a couple? Are they ready to announce it to the world on social media by updating their relationship status? These are the things teens discuss when they use the term DTR.

Deepliking

Deepliking is a way for your teen or others to show that they like someone by scrolling through old social media posts and liking them. These likes are usually on photos and posts that are months or sometimes even years old.

Benching

Benching, or breadcrumbing, occurs when someone a teen has been dating or talking to suddenly stops agreeing to meet in person. However, the person still contacts your teen through text, direct message, and over social media.

Basically, these people are trying to keep your teen on the bench while they play out their other options.

Make sure you tell teens to watch out for anyone that keeps them in limbo this way. This is a sure sign of an unhealthy relationship.

Left Me on Read

When your teen is "left on read," what this means is that they can see that their significant other has read their text message, but has not responded—sometimes for days. This is frustrating for teens, and adults for that matter, especially if they were discussing something important.

Leaving someone on read can be a somewhat passive-aggressive way to control the relationship or conversation and an early warning sign for teen dating abuse.

Talking

Perhaps one of the easiest terms to decipher, talking means the couple is getting to know one another and sometimes even casually dating. Both parties are interested in having a relationship and are trying to determine what they have in common and if it should go any further. It also means that they are not yet in a committed relationship but only testing the waters at this point.

IRL

The acronym IRL stands for "in real life" and means that the relationship has progressed from just talking or texting to an actual, in-person date. Most teens only date people they already know offline through school, clubs, or other venues. However, it is common for the beginning stages of flirting to occur online before progressing to an "official" in-person date.

Netflix and Chill

To parents, it may sound like the couple is just meeting to hang out and watch television together. But it could mean that their plan is to meet up and make out or have sex.

If you hear your teen use this term, you might want to investigate a little further to see what is really up.

Jelly

Although not used as often as it used to be, jelly stands for jealous or envious. And even though they are using a different word to describe feeling jealous, the emotions are still the same.

Thirsty

Thirsty means being desperate for something, usually referring to someone's desire to hook up or have sex. For instance, someone might say: "He is so thirsty."

Extra

This term is used to describe someone who is over the top or dramatic. Generally, this is not a complimentary term and is often considered a criticism.

Basic

Like "extra," the term basic is not generally used as a compliment, but instead used as a criticism of another person who tends to like anything that is trendy or popular.

53X

If you see this in your teen's text messages or direct messages, you need to know that "53X" is leet speak for "sex." Leet speak is a form of communication that replaces common letters with similar-looking numbers.

It is a good idea to investigate a little more to see what context it is being used in and what your teen meant by the code.

GNOC

This acronym is short for "get naked on camera" and is often used to pressure someone into sexting or sharing explicit photos.

Turnt

If a teen says they are looking to get turnt or turnt up, this is code for teens wanting to get drunk or high. Beware if you hear this term in the context of your teen's conversation and start asking questions.

Telltale Signs Your Teenager Has Been Drinking Alcohol

Why Teens Use Their Own Lingo

Many people assume that teens use slang or their own lingo to hide things from parents. But while this may be true in some cases, having their own language so to speak is more about identity than it is about keeping parents out.

In fact, some psychologists liken it to fashion. Just as teens would rarely wear their parents' clothing, the same is true about using their words.

Think back to your time as a teen. Did you use your parent's terms to describe things? Probably not very often, if at all. Using your mom's words to describe something could be on par with wearing mom jeans.

For the most part, teens use their own lingo as a way to create their own identity, fit into certain social groups, and express their independence.

But keep in mind that slang is always changing and evolving. What's more, in what feels like no time at all, the list of terms you see above will be outdated and replaced with an entirely new set of terms.

Remember, it is normal to have special phrases and terms to describe things. Every generation has done it. And most likely, they will keep on doing it. After all, parents today were once strange teens and used weird words like "totally" all the time.

What Your Teen Needs to Know About Dating Safely

A Word From Verywell

Aside from understanding what your teen is talking about, knowing the latest lingo that teens use to describe their dating experiences is useful knowledge for parents. Not only does it provide insight into what is happening in your teen's life, but it also equips you with the background information you need to share helpful advice.

For instance, when teens are being ghosted by someone, it can help to have someone put this into perspective for them. Even though teens have a new way of describing what is happening in their world, their needs are still the same. Sometimes it helps to have a little guidance on how to navigate the confusing aspects of dating.

100 Common Text and Social Media Acronyms Used by Teens

Thanks for your feedback!

Verywell Family uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles. Read our editorial process to learn more about how we fact-check and keep our content accurate, reliable, and trustworthy.

Navarro R, Larrañaga E, Yubero S, Víllora B. Psychological Correlates of Ghosting and Breadcrumbing Experiences: A Preliminary Study among Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):1116. doi:10.3390/ijerph17031116

Giordano PC, Soto DA, Manning WD, Longmore MA. The characteristics of romantic relationships associated with teen dating violence. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39(6):863-874. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.009

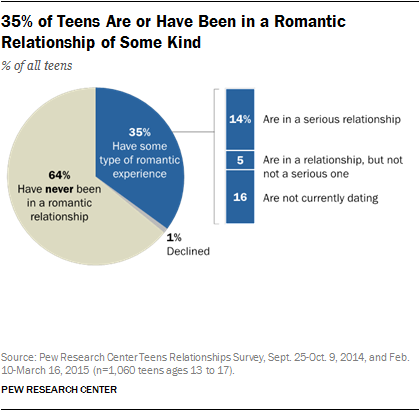

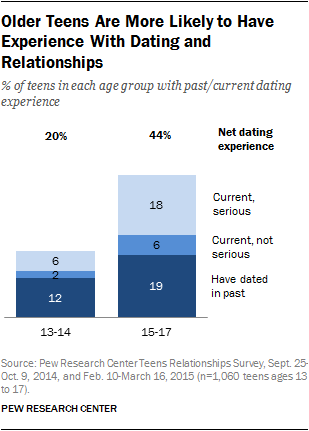

Pew Research Center. Teens, Technology, and Romantic Relationships. 2015.

Fabjančič T. Catch Me If You Can! – Slang as a Social Phenomenon and the Issue of Capturing It in Dictionaries. ELOPE. 2010;7(2):27-44. doi:10.4312/elope.7.2.27-44

There is a lot of debate and stigma that surrounds teen love. Many adults brush teen relationships off, believing that they are unable to stand the test of time. However, this believe is not entirely valid. the average age of marriage has continued to rise from generations past, it doesn’t prove that teen love is not real or that it cannot last. However, it isn’t that simple either.

Some, not all, teen love is real. Determining whether this love will last depends solely on the individuals and if they are willing to develop the feeling of love into true love.

The Difference Between Love and Lust

The first relationships that teens usually experience are referred to as puppy love or a crush. This goes right along with lust. The attraction to the other person is purely physical. There is excitement and energy in the relationship. The feelings are surface level and do not go deeper than that. It is a relationship that is based purely on feelings.

Lust is a normal response that people experience, including teens—but it’s not love. Many teens and adults confuse the two. Lust is based only on the physical attraction, where love is much deeper than that and involves caring about the other person. The relationship may begin because of lust, but real love moves past lust and physical attraction. It is not based on feelings, but on commitment and a decision.

It’s All About the Mindset of the Teen

There are two different ways to look at dating. First, you may be dating because you want to find your life partner. When you have this mindset, you’re careful about the people you choose to date because you’re looking for someone specific. Second, you may be dating because you’re just having a good time and want to hang out with someone. You aren’t necessarily looking to commit, and you may date several people at once.

Your dating mindset will play a major role in determining if your love is real and if it can last. If you’re merely looking for a good time, then you’re likely to end the relationship when fights and challenges naturally arise. You may have feelings of love, but not true love. However, if you’re looking for your future partner, then you may be able to turn feelings of infatuation into feelings of love.

True love requires a certain level of maturity. It’s easy to be attracted to someone. It’s also easy to date someone and truly like them. This may lead to feelings of love, but true love only comes when you’re willing to stand the test of time, even when things get tough. When you’re really in love, you can’t be overly demanding or jealous, nor can you run out every time things get hard. With a little work and a lot of love, however, you can build a relationship that lasts for the long haul.

Can Teen Love Last?

The answer is simple and complex at the same time. Teen love can last—just ask all of the high school sweethearts that are still married decades later. While it’s true that any romantic relationship has its difficulties, teen love has some specific challenges that usually don’t apply to adult relationships.

You Must Know Yourself

One of the biggest challenges in teen love is that most teens are still in the process of finding themselves. When you don’t know who you are, it’s hard to form a healthy relationship. If teens are in a serious relationship while they’re going through this discovery process, they may eventually realize that who they are is not compatible with their significant other. Or, if they are unwilling to admit this, they might try to be someone they’re not to please their partner. This will eventually lead to problems in the relationship.

For teen love to last, the teenagers need to have a high level of maturity at the beginning of the relationship, or they need to be willing to discover themselves together. That means they will support each other throughout this process. When both individuals are committed to growing within the relationship, they can discover their identities without needing to end the relationship. This journey will bring them closer together.

Changing Circumstances

Adults are usually in a more stable place when they begin relationships. When teens start relationships while they’re in school, they’re going to face a trying time as graduation approaches. Teens that are in serious relationships will need to determine if they’re going to end their relationship when they go off to college. They may also choose to forego college, attend college together, or make any number of joint or separate plans. Graduation is a time of major transition for every high school student. Adding a relationship to the mix can make it even more difficult. Many relationships end at this point because teenagers want to see what will happen in the next phase of life.

If It Doesn’t Last

There are many different reasons why teen relationships don’t last; in this way, they’re just like any other relationship. Teen relationships may end because both people may realize they aren’t interested in the same things, that they’re heading out to college, or that they aren’t willing to stick it out when things get tough. Whatever the reason, it doesn’t mean that the relationship and the feelings weren’t real.

Breakups are difficult, and passionate teens often have a harder time dealing with them than adults do. Teens ending a relationship may experience extreme emotions. If you are experiencing overwhelming grief, or other feelings after a breakup, talking to a professional therapist can help.

For Parents of Teenagers

Do not dismiss teen love. Your teenagers’ feelings are just as real as yours. If you dismiss them, you could strengthen your child’s desire for the relationship. They will feel that you don’t understand them, and you will create a distance between the two of you.

As a parent, you want your child to feel free to talk to you about all areas of life, including love and relationships, so you can provide guidance as needed. When you tell them, it’s “puppy love,” that it’s not real, or that it’s not going to last, you risk losing your ability to give advice. Your teen will stop coming to you with questions or sharing information with you.

That said, if you notice signs of an unhealthy relationship, it’s time to step in. It’s normal for teens to want to spend all of their time with their boyfriend or girlfriend, but you should watch for extreme jealousy, isolation, bruises, changes in behavior, a large age gap, and frequent arguments. These are signs that the relationship may not be a healthy one. It’s difficult for people of any age to recognize when they’re in an unhealthy relationship. As the parent, it’s your responsibility to help your child if they’re in this situation.

Tips for Teens in Love

Relationships are difficult. If you’re simply dating “for fun,” then it probably isn’t worth investing seriously in the relationship. However, if you are serious about the other person and would like to see the relationship last, there are a few things you should remember.

- Make sure the feelings are mutual before investing 100 percent. You may be serious about the relationship, but before you get too committed, make sure the other person feels the same way.

- Do not mistake sex for love. Love is more than physical attraction, and having sex is not a way to find love.

- Do not sacrifice all of your friendships for your relationship. When relationships are new, you tend to want to spend all of your time with the other person. Remember that it’s important to have friends outside of your relationship as well. You should also continue spending time with family, and participating in activities that you enjoy.

- Discuss the future together. Do you both feel the same way? What will happen after graduation?

Understanding Teen Relationships With BetterHelp

When it comes to teen love, there are multiple ways that a therapist can support you. For starters, it’s important to know yourself and love yourself if you want to have healthy relationships. If you struggle in these areas, a therapist can help you discover who you are, so you can accept and love that person.

Studies have shown that online therapy platforms can be useful for helping teens manage anxiety, depression, and other issues. According to one study, internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (ICBT) is an effective way toaddress symptoms of anxiety in adolescents. Therapist-guided ICBT is a widely utilized method of helping teens and adults deal with emotions related to love and other aspects of life. It works by helping reframe negative thoughts, so that those with mental health concerns can better manage their interactions and relationships. The study found that ICBT reduced participant anxiety, as well as depression, concluding that even those with severe symptoms can benefit from this form of counseling.